Take Control Of The Secret NINE FACTORS That Really Control Your Life

If we did not already recognize that it is challenging for anyone to build new helpful habits, a story about former US president Barack Obama can help us understand more. It is also worth noting that Obama was not just the first African American president but

the third youngest in over 100 years.

CBS News showed Mr. Obama taking questions from the press shortly after announcing new laws to regulate the American tobacco industry. A reporter asked him several questions about his own smoking habits. How many cigarettes does he smoke every day? Does he smoke in the presence of others?

Barack Obama is regarded by many as a consummate statesman, a highly capable leader, and a powerful role model. But even he admitted that stopping smoking was a “struggle.” “Have I fallen off the wagon?” he said. “Occasionally, yes.”

He added: “I’d say I am 95 percent cured, but there are times when I mess up. Like folks who go to Alcoholics Anonymous…smoking is something you continually struggle with.”

In this article, we’ll explore the science and the simple practice steps you can use to build the sustainable new habits that will make it easier to be your best.

Verbal Persuasion Doesn’t Work!

Changing our habits (the foundations of all human behavior / at least 98% of what you are doing and thinking at any given time) is complex. We often fail because we do not understand the science of behavioral change.

When we try to build a new habit in any area of our life, the default (but faulty) behavior change technique we have been taught is what I term “verbal persuasion.”

We notice an unhelpful habit (e.g., worrying, beating yourself up, procrastination) and persuade ourselves we really DO need to stop. For example, we tell ourselves, “We are beating ourselves up too much…we must stop.” We may even tell somebody else of our intention to stop this unhelpful behavior.

We use the same verbal persuasion technique if we want someone else to change a behavior. You might say: “I think it would be a good idea if you turned up for meetings on time, because this would be helpful for team performance.” But even if people agree

that your behavior change suggestion is a good idea, this is not enough to help people build the new habits that will deliver the change.

The behavioral science is clear: this traditional approach to changing our habits is overreliant on Will Power. Wanting to make a change is not enough to build a new habit. To make sustainable change, we must use insights from behavioral science to create a precise step-by-step approach.

Will Power Is the Conduit for Change—but It Is Limited

All behavior change begins with using Will Power to resist the old habit. For example:

Trigger and Limbic Brain Region rewards: You notice the urge to check your phone, NOW, meaning you will have to break your focus on an important piece of work you need to complete ASAP. This is HUE (Horribly Unhelpful Emotions – the boss of your Limbic Brain) looking for short-term gratification. Having the phone in your eyeline is part of the trigger for your desire to check it.

Routine: You use Will Power to regulate your emotions and resist the temptation of entering the old routine of checking the phone. By doing this, you are starting to create a new routine, that is, when you feel the urge to check your phone, you show resolve and stay focused on the task on which you are working.

But if you only rely on your Will Power, it is likely HUE will eventually win and you will check your phone.

Although Will Power is the conduit for building new helpful habits, it is a limited resource. So we need to use Will Power PLUS behavioral science to secure new habits.

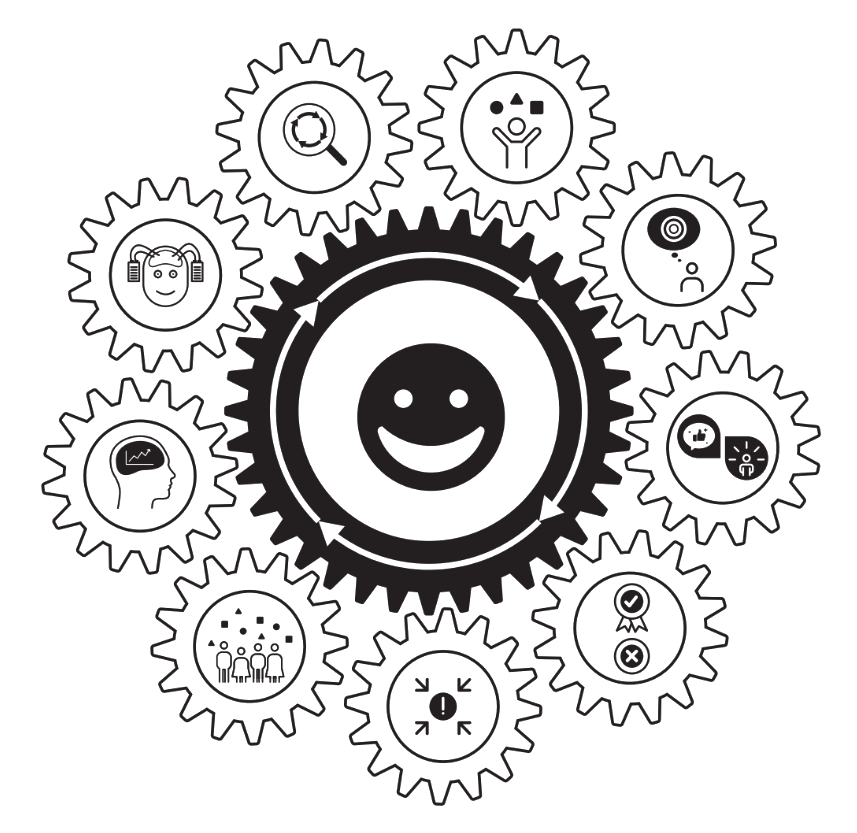

Habit Architecture: The Nine Action Factors Framework

To help people regulate their emotions and supercharge the habit building process, I used the latest insights from behavioral science to create the proprietary Tougher Minds “Nine Action Factors” framework. I use this framework, and the 200+ tactics I have created, to help my one-to-one clients create personal change and my business clients to create habit-based cultural change (i.e., helping them to create a habit-based business strategy that delivers organizational Key Results and Objectives 20%-80% faster than a traditional business strategy). Here I will show you how to use a simple version to help you build new habits that last.

All of the nine factors are interconnected. Here is a simple overview of the nine factors (I will explain each in greater detail later):

1. Habit Mechanic Mindset Factor

Figure 1.1: If you don’t believe you can improve, you never will. The right mindset is essential for changing

your habits.

2. Brain State Optimization Factor (Training; APE Incentive)

Figure 1.2: To successfully build new habits, your brain needs to be neurobiologically ready for change.

3. Tiny Changes Factor (APE Incentive)

Figure 1.3: You can change but only one tiny step at a time.

4. Personal Motivation Factor (APE Incentive)

Figure 1.4: It is easier to change if there is a meaningful reason why.

5. Personal Knowledge and Skills Factor (Routine)

Figure 1.5: Building new habits often requires you to learn new things.

6. Community Knowledge and Skills Factor (Routine)

Figure 1.6: If the people around you already know how to do the thing you want to learn (e.g., manage stress),

it will be easier for you to learn it.

7. Social Influence Factor (APE Incentive)

Figure 1.7: If the people around you are already doing the thing you want to do, it will be easier for you to do it.

8. Rewards and Penalties Factor (APE Incentive)

Figure 1.8: Rewards encourage behavior and penalties discourage it.

9. External Triggers Factor (Trigger)

Figure 1.9: It is easier to do things if you get triggered (reminded) to do them.

Figure 1.10: Activating all Nine Action Factors together makes building and sustaining new habits easier.

Why Do We Need to Know So Much to Build New Helpful Habits?

Many of the thoughts and actions that are unhelpful for our health, happiness, and performance are what I call simple behaviors, like eating donuts, checking your phone too often, and beating yourself up. These behaviors are Limbic Region Brain–friendly and driven by human instincts connected to staying alive, achieving and maintaining social status, and conserving energy. These simple behaviors are increasingly agitated and exploited in the ‘Emotional and Attentional War’ we are all fighting.

Unfortunately, many of the thoughts and actions that are most helpful for being our best in the modern world are what I call complex behaviors, like sleeping well, eating healthily, exercising sufficiently, not dwelling on negatives for too long, and becoming

an outstanding leader. These behaviors are not Limbic Region Brain–friendly. They require us to learn new knowledge and skills and become expert habit builders or, in other words, Habit Mechanics and Chief Habit Mechanics.

The Nine Action Factors are constantly influencing your behavior (for better and for worse), but we are largely unaware of them. To help you take more control over your own thoughts and actions, I’ll show you how to use the Nine Action Factors framework to your advantage.

Using the Nine Action Factors

I use learning to drive as an example to understand more about how we can use the Nine Action Factors to help us build new helpful habits. Just like many of the things we would like to improve, driving is also a complex behavior, which is why it is a good example to use. Even if you haven’t learned how to drive, this example will still make sense. Here are the nine factors and how they influence us when we learn to drive.

1. Habit Mechanic Mindset

Think of mindset as belief and what we believe. People with a Habit Mechanic Mindset believe they can improve anything with practice and take responsibility for being their best. People with an Fixed Mindset believe they are only good at certain things, and

cannot change. If we did not believe we could learn to drive and were not prepared to put the effort into learning, we would not have achieved this milestone. A Habit Mechanic Mindset is essential for learning to drive.

2. Brain State Optimization

In simple terms, this relates to how ready your brain is to learn (i.e., building a new habit is underpinned by learning to do and think in a different way). If you were sleep-deprived and took a driving lesson, you would unlikely be in the right Brain State to concentrate or gain anything helpful from the lesson. Equally, if you are stressed or in a bad mood, it will also be more difficult to learn (i.e.,

motion drives attention; attention drives learning).

If we want to learn something new, we must be in the right Brain State.

3. Tiny Changes

This factor relates to the size or scale of the change we want to make (e.g., lose 15 pounds, get an extra hour of sleep per night, become the best leader in my business). In simple terms, we can make changes to behavior, but we can only make one tiny change

at a time. If we want to learn to do something new, it is far more efficient to do it in stages and focus on making one tiny change at a time. For example, we learn to drive over extended periods and build a surprising amount of tiny new interconnected habits.

We do not simply climb in the car and immediately gain a complete understanding of how to drive. Often, many first lessons just

nvolve the student working out where all the controls are in the vehicle.

So, to best use the Tiny Factor, we should work toward an accumulation of tiny changes and improvements, instead of trying to make a single massive leap of progress. Here are some other examples:

- Want to lose one stone (or 14 pounds)? First focus on losing half a pound.

- Want to get an extra hour of sleep per night? Aim for one minute of extra sleep tonight, then build up to five minutes and so on.

- Want to be the best leader in your business? Start by building one tiny new habit that will improve your leadership.

4. Personal Motivation

It’s easier to make a change or build a new habit if you can connect it to a bigger meaningful goal in your life. In the case of driving, you may have needed or wanted to learn how for work reasons, or to take your children to school, or to be the first qualified driver in your peer group, or some other reason. If we can connect the change we want to make to our bigger goals, dreams, and desires, this will provide motivation and make it easier to keep persisting with difficult changes.

5. Personal Knowledge and Skills

We do not need to acquire new knowledge and skills to eat a donut, but it is often essential for complex behavior change—like learning to drive, improving our confidence, or enhancing our sleep or productivity, etc.

6. Community Knowledge and Skills

What knowledge and skills do our families, peers, and communities have that might help us? Having a parent who knows how to drive can be helpful if you also want to learn (think of free driving lessons in supermarket car parks). A colleague knowing how

to build better stress management habits is helpful if you also want to develop some. The reason I try to make all our insights simple is so they can be easily shared among colleagues and families and across the Habit Mechanic community. The more people

there are in your network who understand the Habit Mechanic Tools and language, the more powerful they become.

7. Social Influence

We implicitly worry about how we are perceived by people we look up to and respect because we want them to like us. In the case of learning to drive, if our parents think that speed limits can be ignored or there is no need for car insurance, they won’t be

good role models for us as learner drivers.

8. Rewards and Penalties

The Limbic Regions of our brain are strongly influenced by rewards and penalties. These can be social, intrinsic, or extrinsic. In the case of driving, people are rewarded for driving well and penalized for driving poorly. If you drive well, you will eventually pass

your test and gain a full license (a reward). A long period of accident-free driving usually means a lower motor insurance premium (another reward). But breaking the speed limit can mean a fine, points, higher insurance, and, if you do it too many times, a

lost license (in other words, penalties!). We can use rewards and penalties to help us build new helpful habits.

9. External Triggers

External triggers in our modern world can be physical and digital. The smartphone is one of the most powerful external triggers ever designed. In a vehicle, we are surrounded by triggers. The speedometer shows us how fast we are traveling. A line in the middle of the road indicates which side we should drive on. A pedestrian crossing will remind us to stop. All of these are triggers, and they are often loaded with rewards and penalties.

Summary of the Nine Action Factors

Think of each factor like a switch that you can turn on or off. If you “turn the switch on” for each factor, they will work for you, and building a new habit will become easier. But if the “switches are turned off,” each factor will work against you, and building the habit

will be more difficult. Learning how to turn each switch on is an essential Habit Mechanic skill, and something I will help you to learn how to do.

This was adapted from chapter 18 of Dr. Jon Finn’s best-selling book, The Habit Mechanic (currently you can get a paperback copy for FREE + shipping)