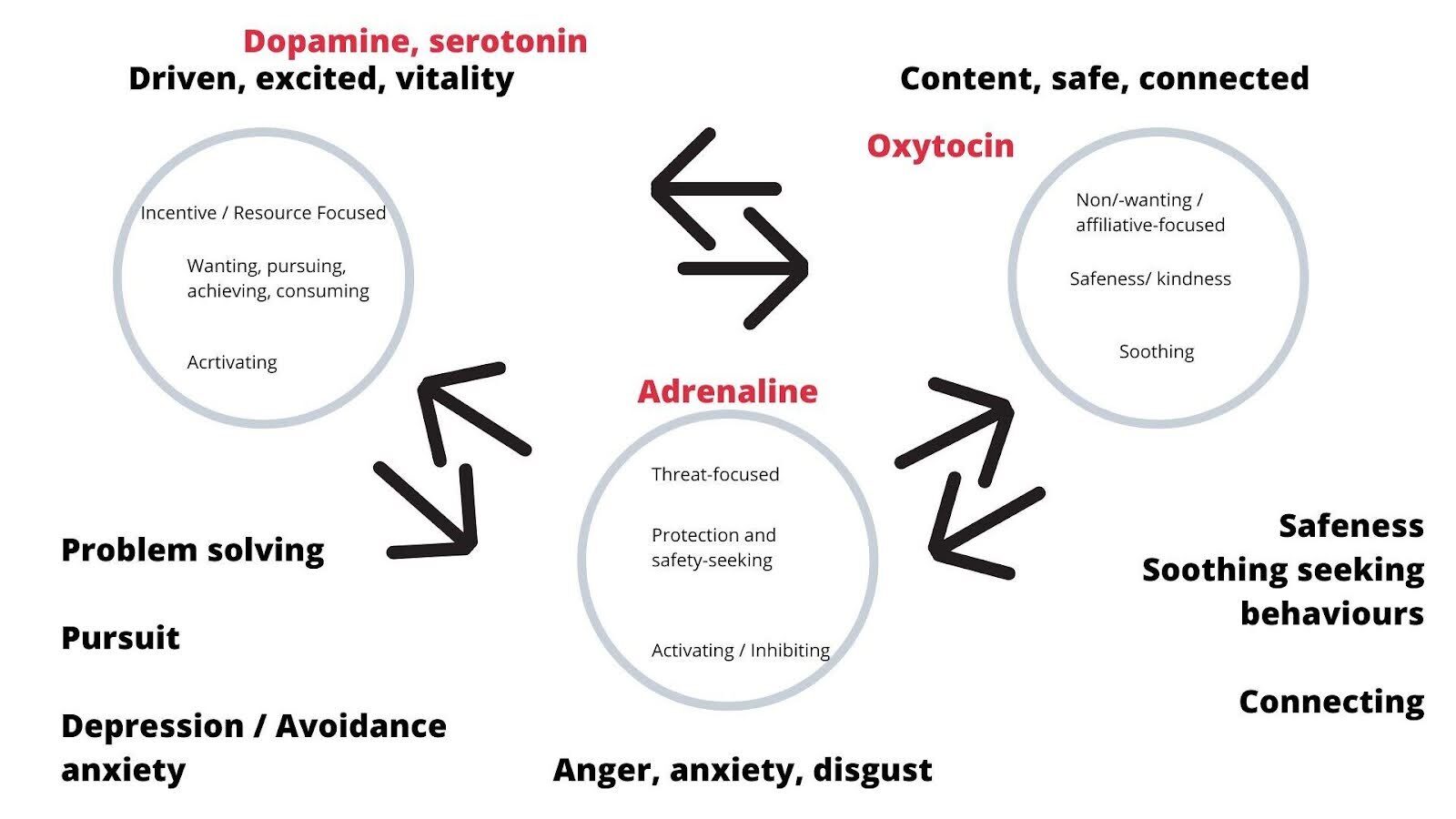

Dopamine, often called the “pleasure chemical,” plays a huge role in how we experience pleasure and reward. It fuels one of the most used emotional regulation systems, the reward/goal-oriented system. But there’s so much more to dopamine than just making us feel good.

Let’s take a deep dive into the world of dopamine, exploring its many functions, its role in evolution, and how it impacts our everyday lives and long-term goals.

The Evolutionary Perspective

To really get why dopamine is so important, we need to look at it through the lens of evolution. Early humans had to be super-efficient with their energy (activity) because food was scarce. Doing anything that didn’t ultimately payoff could be dangerous. Dopamine helped our ancestors predict the potential success of an activity based on past experiences and current beliefs. If an activity was predicted to be successful, then dopamine began to stimulate us (in a way we call motivation) heightening our energy toeards movement towards that ctivity. Once successfully completed, bigger doses of dopamine release. This provides us with the sensations of success and pleasure that have led to dopamine being referenced as the pleasure chemical. Ijj nfact, dopamine provides us with a sense of accomplishment or power. In other words, it helps ego expamsiona nd inflation. This is cery important. Th egreater amounts of dopamine, the higher our internal sense of perceived axccomplishment and ability. This helps buffer us from anxiey and stress, because it leads us to make positive predictions about our ability and hence, provides us with a sense of confidence wich would then spill over into more positive predictions about activities or tasks we have never tackled before.

Imagine our early ancestors leaving their safe caves. They faced all sorts of dangers, from predators to injuries that could turn deadly. But taking these risks often led to big rewards like building shelters, farming, and forming social bonds. Dopamine played a key role by motivating them to engage in these risky activities with the promise of a reward when they succeeded.

Dopamine as a Success Predictor

Dopamine is like our brain’s success predictor. It helps assess our skills and confidence before we start an activity. It mobilizes energy in our bodies, pushing us toward our goals. When we complete an activity successfully, dopamine is released, making us feel good and more likely to do it again. This process is crucial for learning and developing behaviors that help us survive and thrive.

But. unlike we have thought for many years, dopamine doesn’t just seek to assess reward and success, in fact, dopamine is also implicated in coding for failure predictions and then creating an opposing motivational force which is experienced as s lack of motivation or actual motivation to avoid an activity.

Dopamine, Depression, and Motivation

So, dopamine isn’t just about pleasure; it’s also linked to depression and low motivation. We need optimal levels of dopamine to stay motivated and engaged in activities. Low dopamine levels can lead to a lack of motivation and symptoms of depression. This connection is especially clear when we face challenges or threats.

For instance, if you think you’re going to fail at something, your dopamine levels might drop, leading to procrastination or avoidance. This reaction makes sense when you consider our evolutionary past—avoiding risky activities after a failure could boost survival chances. Understanding this mechanism helps explain why we sometimes struggle with motivation and how it’s tied to our perception of success and failure.

Dopamine in Modern Life

Even today, the principles of dopamine’s function are still relevant. Our motivation to complete tasks, whether it’s finishing a work project or hanging out with friends, is heavily influenced by our dopamine levels. If we see an activity as too difficult or likely to fail, our motivation drops, or we may become strongly motivated to avoid an activity. This can lead to procrastination or avoidance, much like how our ancestors would avoid activities that seemed too risky.

To tackle this, it’s important to create an environment that consistently triggers dopamine release. Setting achievable goals, celebrating small successes, and balancing work with relaxation and social activities can all help. By scheduling tasks and recognizing when we complete them, we can encourage dopamine release, which boosts our motivation and sense of accomplishment. Dopamine is entirely reliant on our subjective assessment of success. Depending on how we “hashtag” our experience and actions will determine whether that activity will lead to greater dopamine release, and therefore become an activity that we perform more repetitively and with greater motivation over time. Inversely, “hash tagging” your activity as not good enough, meaningless, or as a failure (perhaps because of what metric you are using to assign success or failure) then that activity becomes harder to engage in next time, because it will stimulate the avoidance system.

Boosting Your Dopamine Levels

Here are some practical ways to enhance your dopamine levels:

- task Scheduling: Plan and schedule your tasks, even tasks that you do as part of your routine and you don’t currently consider a big deal When your brain sees a completed task, it releases dopamine, giving you that feel-good sensation. This can include work tasks, exercise, or even leisure activities like binge-watching your favorite show.

- Celebrate Small Wins: Take time to acknowledge and celebrate your small achievements. This reinforces positive behavior and makes you more likely to repeat it.

- Process Vs Outcome Oriented: If you are going to make the effort to perform an activity than the effort it takes to do that activity should be the metric, we use to feel successful and accomplished. Try shifting your metric system from the outcome of your efforts and start to focus more on the step-by-step process that it takes to usually achieve said outcomes. The issue with outcome-oriented success metrics is that often outcomes are reliant on factors that can be outside of our control or based on external sources of validation. This then means that you can be working as hard as you did last week but the outcome is no longer being validated by the external environment. If your success metric is outcome oriented, then you become completely reliant on external validation for your dopamine. I don’t know about you, but I do not think that this would always lead to fair assessments.

- Balanced Activities: Mix up your routine with work, relaxation, and socializing. Regular social interactions can boost dopamine levels, as we’re wired to seek and maintain social bonds.

- Positive Self-Talk: Be mindful of your self-talk. Encouraging and positive thoughts can enhance dopamine release, while negative self-talk can increase stress and lower motivation. How you talk to yourself determines whether the brain will categorise your efforts as successful or failures, and therefore be responsible for dopamine release.

- Exercise: Regular physical activity is a powerful way to boost dopamine. It not only promotes physical health but also enhances mental well-being by increasing dopamine production because it increases our perception of being strong enough to navigate our environment.

Wrapping It Up

Dopamine is a vital neurotransmitter that does so much more than just make us feel good. It predicts success, motivates us, and influences our mood and overall well-being. By understanding its complex functions and using strategies to keep our dopamine levels in check, we can significantly enhance our daily lives and achieve our long-term goals. So, celebrate those small wins, stick to your schedule, exercise regularly, and maintain a balanced lifestyle to harness the power of dopamine for better motivation, productivity, and happiness

Lerner, T. N., Holloway, A. L., & Seiler, J. L. (2021). Dopamine, Updated: Reward Prediction Error and Beyond. Current opinion in neurobiology, 67, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.10.012

Papalini, S., Beckers, T., & Vervliet, B. (2020). Dopamine: from prediction error to psychotherapy. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 164. doi:10.1038/s41398-020-0814-x

Magnon, A. P., . . . Wanat, M. J. (2019). Pattern of dopamine signaling during aversive events predicts active avoidance learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(27), 13641-13650. doi:doi:10.1073/pnas.1904249116